Colin Conrad has spent years researching the way the human brain interacts with technology and how learning can most effectively be achieved in the digital realm. Yet, when the COVID-19 pandemic arrived last March, he had never taught an online class himself.

Now, with the Winter 2021 term underway and a few successes under his belt, the assistant professor in HÂţ»â€™s School of Information Management (SIM) finds himself reflecting on that irony.

“Believe it or not, even though my research and my PhD dissertation was on online lectures, I had not taught online before last semester,” he says. “I was teaching my data science course that semester, and when the pandemic hit in March we were wondering if we’d be coming back the next week.”

Turns out, they did not.

Dr. Conrad took swift action, radically changing his teaching style from an in-person lecture system to recorded lectures that were designed to be experienced asynchronously (meaning, not at a specific time but whenever it suited students). In his graduate-level Information Systems Management class, he supplemented these lectures with two synchronous labs at designated times to encourage active learning.

“It was well received and the projects the students did were what I expected. That shift is what grounded the teaching philosophy of the fall semester.”

Keeping it concise

Dr. Conrad was successful early in the pandemic. Much of this, he says, is likely owed to his research background in cognitive processes and educational technology. There are practical benefits to asynchronous lectures, too, such as being more accessible to students in different time zones.

“I had a lot of international students who were working overseas, and for them, doing synchronous classes is truly awful. They either have to be participating live at strange hours, or they have to watch recordings. But watching recordings of a synchronous lecture is cognitively draining. They’re not designed to be watched — they're designed to be interacted with.”

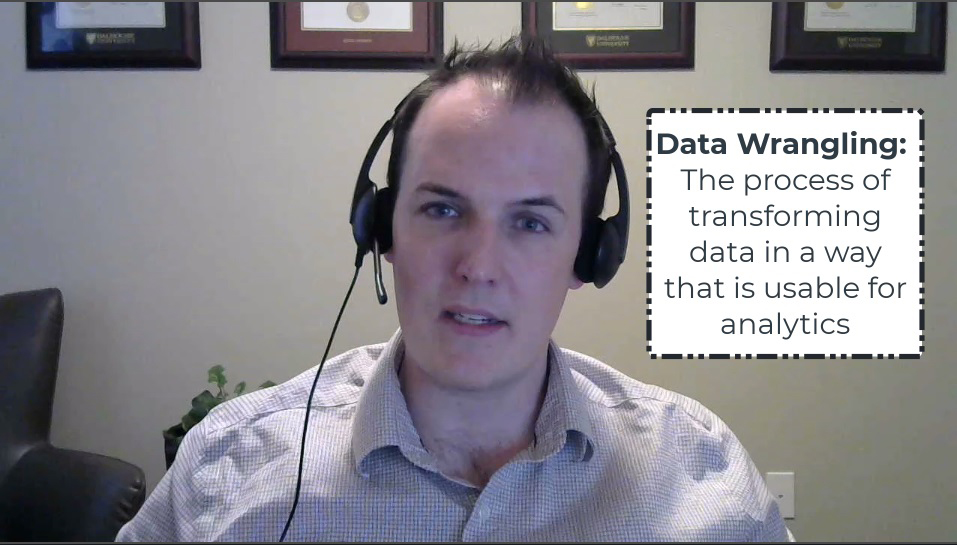

Dr. Conrad, shown right during a lecture, says that by recording asynchronously, you can avoid time wasted on things like recording “ums” and ”ahs,” and fiddling with technology like PowerPoint slides. He also says it can be frustrating for students that have to listen to others asking questions when they can’t ask their own. Overall, Dr. Conrad says he saved significant time in delivery by using concise, recorded lectures. “I had the same lectures I used to do delivered asynchronously in 20–30 minutes, rather than 80,” he says.

This time efficiency is at the crux of Dr. Conrad’s success, a fact he owes to years of extensive research. “I did research in mind wandering, in which subjects watch really long lectures. We wanted to figure out why Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are not effective, and one of the reasons for this is that the mind starts to wander after about 20 minutes.

“Not only is there a lot of literature supporting this, I have a lot of quantitative evidence from my own experiments that once you hit that 30-minute mark, people’s thoughts go inward and they’re not as engaged with the external world — at least in a MOOC format.”

From theory into practice

Dr. Conrad says he bases his course design on three cognitive e-learning theories. The first is the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, which is about reducing cognitive load on students. “Brains have a limited capacity to process information,” he says. It is this theory that prompted him to record concise lectures.

The second theory is active learning. “Every week, I have some sort of active-learning exercises that students must do, which compliments the lectures.”

The third theory is social-presence theory. “The core of this theory is that learning is a social experience,” says Dr. Conrad. “Being able to have some synchronous experiences is essential, like the synchronous labs in my graduate classes. Students found those extremely informative. They were able to do group work and meet on their own time, so there was a social element to the class.”

Dr. Conrad has limited the number of synchronous labs in his classes to two. This is to prevent difficulties for students in different time zones who may find it hard to participate during unconventional hours. Likewise, he provides two offerings of these labs when necessary – one in the morning and one in the late afternoon – to allow students to choose times that are better for them.

Active learning and one-on-one play a part

Dr. Conrad’s labs consist of assignments that students can discuss and work on through Microsoft Teams. “My labs are group-based and they have to be done synchronously.”

Dr. Conrad likes to use a game format in his labs. “One of them was a card-sorting exercise that they had to solve as a group. That was used to teach the concept of business processes. For the second one, we used a tool called ERPsim, in which they run virtual dairy cooperatives in a competitive environment.”

He says that asynchronous lectures wouldn’t be appropriate without that active component. “If I was teaching, say, a philosophy class, I think asynchronous lectures would be awful. So, it really depends on what you want to teach.”

When asked if he has any advice for faculty, he says, that in addition to considering shorter, asynchronous lectures, being available to students can make a world of difference in ensuring their success.

“Be willing to meet students one-on-one, even for fifteen minutes.”

As for students, Dr. Conrad encourages them to be proactive. “It can be really difficult to be proactive, and to ask questions on a platform like Microsoft Teams. But if you have a question, especially in a large class, chances are others have it, too.”