To the casual visitor, the park that sits at the northern tip of the Halifax peninsula could be mistaken for just another urban green space, good for a stroll with a dog or a scenic picnic.

Dig into a bit of local history, though, and you’ll find that a mere 50 years ago or so this area was the epicentre of a much different kind of place — a tight-knit community complete with houses, businesses, a school, a church, and even a post office.

Africville, named for the descendants of the American slaves who settled there in search of employment during the mid-19th century, met its unfortunate end in the late 1960s and early 1970s when city officials relocated residents and tore down the structures in the name of urban renewal. Now, decades later, the destruction of the community of Africville is widely recognized for what is was — a major historical injustice against African Nova Scotians.

This acknowledgment didn’t happen overnight, though. It wasn’t until 1996 that the federal government stepped up to recognize the story of Africville by designating the area a National Historic Site. And it took the Halifax Regional Municipality until 2010 to make an official apology for its actions, despite the United Nations’s declaration six years prior that the treatment and destruction of Africville constituted a crime against humanity.

This year, on the 10th anniversary of the city’s apology, Nova Scotia honours (Feb. 17). We spoke to three Dal faculty members familiar with this bleak chapter in the province’s history about why it continues to be an important story to tell and where to learn more.

The next generation

When Shauntay Grant decided to create a book about Africville several years ago, she took a unique approach, focusing primarily on celebrating the many  experiences children — both past and present — have had in the community. Activities such as rafting, fishing, football, berry picking are highlighted, as are more recent events such as the annual Africville Reunion Festival.

experiences children — both past and present — have had in the community. Activities such as rafting, fishing, football, berry picking are highlighted, as are more recent events such as the annual Africville Reunion Festival.

But , which was short-listed for the Governor General’s Literary Award in 2018, also touches on the razing of the community and the injustice that was done.

“When I first started sharing the book at elementary schools, I was concerned about addressing this part of Africville’s history with second and third graders,” says Grant, an assistant professor of creative writing at Dal. “But the book led to fascinating conversations around themes of community, displacement, racism and injustice, as well as a genuine interest among the students to know more about Africville.”

Grant says the project has given her an appreciation for the importance of having difficult conversations with young learners.

“It sparks meaningful reflection and deep debate around things that matter and helps prepare them for the conversations that will no doubt surface later on,” she says.

Where to learn more: “Tłó±đ hosts visitors and events all year round and is an interactive educational space. The is also an opportunity to interact with the Africville community, including former residents.”

Community as classroom

Each year, Barb Hamilton-Hinch takes her students on a series of excursions as part of her seminar class on diversity and inclusion. One such outing is to the lands where the former community of Africville was once located on the shores of the Bedford Basin.

“We go to spaces where the populations we are studying either live or were historically connected to,” says Dr. Hamilton-Hinch, an assistant professor in the School of Health and Human Performance. “It’s more impactful for students to be able to visualize and be in a space where what I’m teaching about becomes more real.”

She says a lot of students don’t realize just how close Africville was to Dal and the city’s downtown. And while there are few physical remnants of the community that was once there, signage, a sundial memorial and a museum modeled on the Africville community church help convey what was once a vibrant community.

“Tłó±đ story of Africville fits very well in my courses. I look at a lot of communities that have been marginalized, from Indigenous communities and persons with (dis)Abilities to the LGBTTQ2+ and African Nova Scotia communities,” she says. “I make sure that my classroom is not just on Dal’s campus, that it is out in the community.”

Dr. Hamilton-Hinch also uses traditional oral history as a way to give her students a glimpse into the history of the place, enlisting older members of the Africville community to serve as guest speakers.

Where to learn more: Dr. Hamilton-Hinch recommends watching , the National Film Board’s 1991 production featuring interviews with former residents, their descendants and city officials. She also suggests reading Jon Tattrie’s book , which tells the story of Eddie Carvery — the protestor who stood up to eviction orders for more than five decades with intermittent occupation of land in his birthplace.

Africville and environmental racism

Ingrid Waldron's work on environmental racism examines how marginalized communities across Nova Scotia, particularly African Nova Scotian and Indigenous ones, are disproportionately impacted by polluting industries.

Dr. Waldron, an associate professor in the School of Nursing and director of the ENRICH (Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities & Community Health) Project, often uses Africville as a historical case study of a community that suffered due to this type of structural oppression.

Dr. Waldron, an associate professor in the School of Nursing and director of the ENRICH (Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities & Community Health) Project, often uses Africville as a historical case study of a community that suffered due to this type of structural oppression.

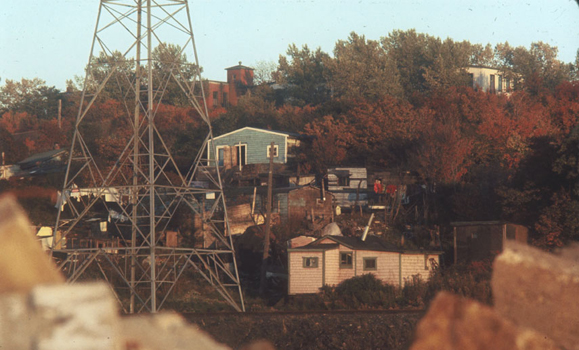

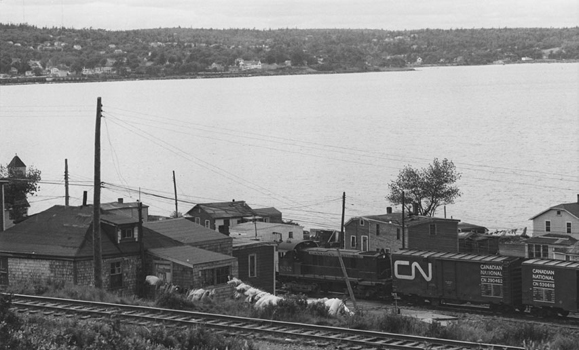

“It’s an example of environmental racism because various hazards were placed in the community when Africville residents were expropriated from their community,” she explains. “What was left were a lot of different types of environmental hazards such as a fertilizer plant, a slaughterhouse, a tar factory, a stone and coal crushing plant, a prison, three systems of railway tracks and an open dump.”

As a health researcher, Dr. Waldron also raises the potential impacts the forced relocation may have had on people’s wellbeing intergenerationally. While she doesn’t know of any formal research studies done looking into the health impacts, there is anecdotal evidence that African Nova Scotian descendants have been traumatized by the experience.

"Although it was a low-income community, there was a strong sense of community among residents," says Dr. Waldron, "and when people’s sense of community is taken away, it can lead to significant health and mental health issues, especially since we know that social support networks are a key social determinant of health."

Where to learn more: “Last year, an environmental science student created anĚý for the ENRICH Project, which can be found on the project’s website.Ěý The map uses text, photographs, maps, audio, video and social media links to tell the story of Africville. It’s a great educational tool, especially for professors and teachers who are interested in teaching about Africville in their classroom. It’s a kind of 'one-stop shop' of tools and resources that can be used to teach about Africville in creative ways using different approaches."

Ěý