Sciographies is a radio show and podcast about the people who make science happen, brought to you by the Faculty of Science and campus-community radio station CKDU. This article is the first in an eight-week series that features excerpts from each new Sciographies episode this fall. You can find Sciographies on Apple and Android podcast apps, by tuning in to CKDU 88.1 FM in Halifax at 4 PM Thursdays (until October 31), or by visiting dal.ca/sciographies.

It was only fourth grade, but Sara Iverson already knew what she wanted to do with her life. The moment of clarity came to her during a family vacation spent exploring Canadian and US national parks. Dr. Iverson, a lover of nature and animals, decided then that a career in wildlife biology and conservation was the right path for her.

Now Dr. Iverson is a professor in the Department of Biology as well as the Scientific Director of the Ocean Tracking Network. She’s also a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada — an honour that recognizes her life’s work studying physiological ecology. Her research takes her to remote locations in North America and the Arctic to study seabirds, seals, sea lions and polar bears in their natural habitats. Mattel and National Geographic even chose her as the role model for their recently released polar marine biologist Barbie. It was an initiative Dr. Iverson was happy to partner on because of the toy’s ability to reach young girls who imagine themselves with scientific careers one day, just like she once did.

In this week’s episode of Sciographies, host David Barclay sits down with Dr. Iverson to talk about her upbringing in Michigan, her fascinating path through university and grad school, what it’s like to work in the field with wild animals, and how to tag sharks and track them for studies that inform conservation policies. Here are some excerpts from that interview with Dr. Iverson.

On knowing her dream career at such an early age…

Iverson: From when I was born, I was just fascinated with animals. I think by kindergarten I had decided I was going to be a veterinarian. But then that all changed. In early fourth grade, my parents took us on a trip across the top of the United States and Canada and we visited every national park we could get to: Yellowstone, Glacier and Banff. There, they took us to some of these nature talks and I learned what a naturalist was. That's when I decided I wanted to do some kind of nature science. And I never wavered.

Barclay: Fourth grade? That’s perseverance and dedication.

Iverson: School itself was pretty hard for me (in grade school and junior high, I think). I wasn’t very good at test-taking and memorizing the things I needed to. It took me awhile to kind of get my ‘sea legs,’ as it were. But it never caused me to waver in knowing what I wanted to do — it was just [a question of] how to get there.

A young Dr. Iverson (middle) at Yellowstone National Park with her siblings during that special family vacation.

On her grad school field research experience…

Iverson: [My supervisor] was really interested in mammalian lactation. We started a project on California sea lions. So, I spent my summers out on San Nicolas Island, the outermost of the Channel Islands, doing work on mother-pup pairs and trying to understand energy transfer, pup growth, fat metabolism.

Barclay: So you’re out in the Channel Islands studying all these concepts. But what does that work actually look like?

Iverson: The island was uninhabited, except for this small Pacific missile test station on the far end. Marine mammals are protected there, so we were the only ones allowed out on these far edges. Every day I would hike about three miles out to where the main sea lion colonies were, and I would catch pups. The whole purpose was to study energy intake (which is the same as the energy output of the mother). You catch the pup, weigh it, and then you give it a dose of what's called deuterium oxide (which is heavy water). You let it equilibrate over a 2-3 hour period, and then you take a blood sample - now you've got the enrichment. Then you let the pup go. The interesting thing about sea lions is that the mother can only produce milk for about two days at a time, then she has to go back to sea to feed. She may be gone for 3-4 days before she comes back. So the mom and pup reunite, and then a couple of weeks later I would try and catch the same pup, take a blood sample and its weight... It's a complicated set of calculations, but by knowing the milk composition, the dilution curve, and the weight gain, you can actually determine, really accurately, energy intake and milk intake.

Barclay: How would you find the same pup? Do they hang out in the same spot, or do you recognize them?

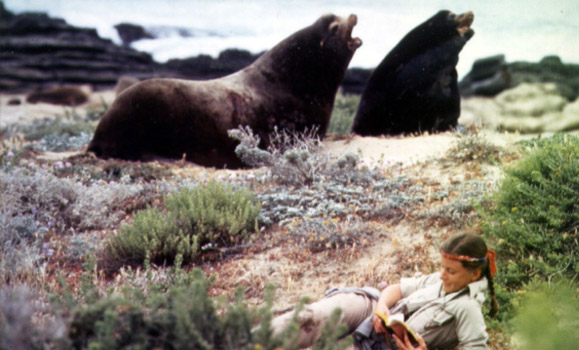

Iverson: We marked them. What’s nice about the sea lions is their pups have very dark brown fur. Before we got on the island we would go to a beauty store and get peroxide bleach. So, we would just bleach mark them. It was permanent until that pup molts. We would go out with binoculars and spot it. Then you would have to crawl on your belly because the minute you stand up, you spook the whole colony and you also lose the pup. So you just crawl on your stomach, through seal feces and everything else, until you get close enough that you think you're going to get it. And then you stand up with a net and hope for the best!

Dr. Iverson hiding behind a sand dune pretending to relax while a fight broke out between two male sea lions during her graduate research in the Channel Islands.

On the significance of being a role model…

Barclay: I need to know: what gave you a bigger feeling? The Royal Society fellowship… or the Barbie?

Iverson: [laughs] Well, that’s a tough question. They’re two very different things. But I would say that I think it's really important for scientists to participate in outreach, whatever form that takes. Because [if you don’t], you're simply not going to get people to care about the world around them and what they need to be thinking about in order to protect things. I think it's our responsibility because we get funded to do this work. It's really important to communicate to people, and that communication comes in all forms. And so, you know, Barbie is one of them, I guess!

*These excerpts were edited for length and format.