Are you a John person or a Paul person?

That’s the thing about the Beatles: despite being perhaps the most beloved rock band of all time, they’re as well known for their individual personalities as their collective work.

‚ÄúPeople have favourites: John or Paul, or perhaps George or Ringo,‚ÄĚ says Beatles fanatic and H¬ĢĽ≠ Math professor Jason Brown. ‚ÄúAnd they cling strongly to what that person‚Äôs contribution was to the Beatles.‚ÄĚ

Which can get tricky at times, given that the vast majority of the band‚Äôs songs are credited to ‚ÄúLennon-McCartney‚ÄĚ regardless of which of the two may have written it. As well, especially on earlier Beatles material, there was often a great deal of collaboration and editing done between the two songwriters ‚ÄĒ¬†and many cases where the recollections of exactly who wrote what differ.

The question of authorship is one of the many Beatles-related ponderings that have tickled Dr. Brown‚Äôs mathematical mind over the years. Now, together with Harvard statistician Mark Glickman, he‚Äôs put together a study aiming to settle some long-standing Beatles debates ‚ÄĒ with math.

The math behind the music

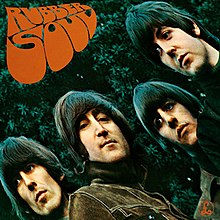

The study, , is an exercise in stylometry: using statistical techniques to determine authorship. With the help of Harvard student Ryan Song, Drs. Brown and Glickman analyzed the entire Beatles catalogue up through 1966‚Äôs Revolver, going through the scores and recordings for every song. (‚ÄúThere seems to be a change in styles after Revolver,‚ÄĚ says Dr. Brown, noting as well that Lennon-McCartney songwriting partnership became a bit more disparate. ‚ÄúSo it seemed like a good breaking point.‚ÄĚ)

What the researchers were looking for were songwriting patterns that disguised McCartney or Lennon’s work: things that each of them did, consciously or unconsciously, that left fingerprints on the songs. The fact that there are about 70 or so Beatles songs (or portions of songs) from that era on which the authorship isn’t disputed, based on interviews over the years, gave the researchers a starting point to identify those patterns and, from there, analyze songs where there’s some debate.

Take, for example, a Beatles classic from Rubber Soul which ranks 23rd on . Sung by Lennon, ‚ÄúIn My Life‚ÄĚ is a song where the recollections of the two songwriters differ as to how it was written. Lennon (who was killed in 1980) credited McCartney with the song‚Äôs harmony part and the middle-eight, but McCartney has claimed in the past that he wrote the majority of the music himself.

Take, for example, a Beatles classic from Rubber Soul which ranks 23rd on . Sung by Lennon, ‚ÄúIn My Life‚ÄĚ is a song where the recollections of the two songwriters differ as to how it was written. Lennon (who was killed in 1980) credited McCartney with the song‚Äôs harmony part and the middle-eight, but McCartney has claimed in the past that he wrote the majority of the music himself.

The math sides with Lennon on this one: the analysis found just a 0.018 per cent probability that McCartney wrote the music for ‚ÄúIn My Life.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúThat particular song generates a bit of emotion on both sides because it‚Äôs considered such a great song,‚ÄĚ says Dr. Brown. ‚ÄúBut there are other songs like where many believe it‚Äôs a Lennon song, but our study shows it to be almost certainly written by McCartney.‚ÄĚ

Finding the pattern

So what sort of patterns distinguish the two songwriters?

‚ÄúPaul, perhaps because of his larger vocal range, often has big skips in terms of melody notes,‚ÄĚ Dr. Brown says, offering one particular example. ‚ÄúFor instance, in ‚ÄėLove Me Do‚Äô ‚ÄĒ¬†the end of the chorus ‚ÄĒ¬†Paul sings the top line and then jumps down an octave. In ‚ÄėEleanor Rigby‚Äô he does the opposite thing. John doesn‚Äôt do that to the same degree.

‚ÄúOn the other hand, John liked, chord-wise, to go between what‚Äôs called the tonic ‚ÄĒ the base chord of the key ‚ÄĒ¬†to the relative minor. He does it in ‚ÄėRun for Your Life,‚Äô ‚ÄėIt‚Äôs Only Love‚Äô ‚ÄĒ it‚Äôs a typical move for him. I think it‚Äôs a sense of ambiguity in the key:¬†is it the major or the relative minor? He liked that sort of ambiguity in his songwriting.‚ÄĚ

This isn‚Äôt the first time Dr. Brown has applied his mathematical expertise to unlock long-argued Beatles lore. Ten years ago, he earned international attention for his work using a mathematical calculation called Fourier transform to try and identify how the oft-imitated, never-quite-duplicated opening chord of ‚ÄúA Hard Day‚Äôs Night‚ÄĚ was played. (The answer, he found, was a piano note buried in the mix.) He also took to the pages of Guitar Player magazine to write about George Harrison‚Äôs solo on that same song, and how the math shows it was initially performed at half-speed and sped up to match the rest of the recording.

His newest project has been generating headlines around the world over the past week ‚ÄĒ¬†in , ., , and beyond. (The day he spoke with Dal News he had three other interviews lined up.) And if you think that all of this effort to unlock Beatles‚Äô secrets takes some of the fun out of rock ‚Äėn‚Äô roll, Dr. Brown couldn‚Äôt disagree more: he finds, in the math, even more evidence of the band‚Äôs greatness.

‚ÄúFor a lot of people, the music is so eternal and so fresh that it‚Äôs like it‚Äôs just yesterday ‚ÄĒ to pardon the pun,‚ÄĚ he says with a laugh, when asked why his research on the Beatles seems to generate such attention. ‚ÄúThe Beatles hold a special place in people‚Äôs hearts and minds. I‚Äôm still captivated by the brilliance of their songwriting, like no other band. Even after all this analysis, it still excites me.‚ÄĚ