More than ever, Canadians are turning their attention towards the impact of opioids on their communities.

Labelled a “crisis” in the media, and by the Government of Canada, there has been a dramatic rise in the number of overdoses and deaths through opioid painkillers like fentanyl and oxycodone. In 2016, there were more than 2,800 opioid-suspected deaths in Canada, with an expectation that the final number for 2017 will be well above 3,000.

“It’s such an important health topic facing Canada right now,” says Sherry Stewart, HÂţ» professor cross-appointed to several departments and one of the principal investigators with the Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse (CRISM) — a national research consortium looking at substance misuse.

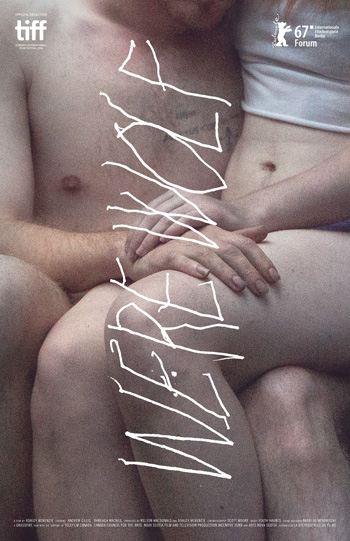

She’s also a panelist at an event next week hosted by Dal’s NTE Impact Ethics group. Paired with a screening of the film Werewolf — the acclaimed Nova Scotia feature film by director Ashley McKenzie about two young people undergoing methadone treatment — the event on Monday, June 11 (Paul O'Regan Hall, Halifax Central Library, 6 p.m.) hopes to shine a light on opioid use disorder and related health and social issues.

She’s also a panelist at an event next week hosted by Dal’s NTE Impact Ethics group. Paired with a screening of the film Werewolf — the acclaimed Nova Scotia feature film by director Ashley McKenzie about two young people undergoing methadone treatment — the event on Monday, June 11 (Paul O'Regan Hall, Halifax Central Library, 6 p.m.) hopes to shine a light on opioid use disorder and related health and social issues.

Event details: Werewolf screening / panel discussion

Ahead of the event, we spoke to a few HÂţ» experts on the subject, to discuss the opioid challenge from a variety of different perspectives and what it means to Canadian communities.

Sherry Stewart

Professor, Departments of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, and Community Health & Epidemiology

The traditional stereotype of the opiate user may be the addict on the street overdosing and dying. But Dr. Stewart focuses on the other end of the spectrum: at-risk youth and new users.

Trained as an alcohol-addiction specialist, Dr. Stewart has expanded her research over the years into other areas of addictive behaviours, including prescription drug misuse. Misuse includes taking a psychoactive medication without a prescription, using a prescription incorrectly (e.g., via a different route of administration), taking larger doses than prescribed, mixing them with other substances and using it for inappropriate reasons — all risks of relevance to potential opioid users.

“There are always going to be new cases unless we can get at the root and prevent new cases from emerging,” she says. “That’s why prevention is so important.”

“There are always going to be new cases unless we can get at the root and prevent new cases from emerging,” she says. “That’s why prevention is so important.”

In late 2017, CRISM received a large, directed funding opportunity through the Emerging Health Threats Research Fund to study ways to address the opioid crisis in Canada. This funding is being distributed across 12 working groups, each addressing a different aspect of the opiate crisis, across a five-year period.

Dr. Stewart’s working group — led through CRISM’s Quebec-Atlantic node — has begun by comparing different approaches to prevention and early intervention in Canada’s provinces and territories as a way to spur new approaches. Few such programs have been designed or evaluated to prevent opiate misuse specifically.

Her working group will also be facilitating forums with high-risk youth and those who recently started using, asking questions about how they perceive different interventions, how interventions should be adapted to work with their age range or what barriers exist for them to be accepted by youth.

“It’s really going to be about young people’s perspectives because we really want to include their insights when we make any changes to interventions and before we try to use them,” she says.

As part of a separately funded CRISM project, Dr. Stewart and her colleagues will be testing an early intervention program called Preventure in high schools across Canada. First developed by Dr. Stewart and her colleagues more than a decade ago, the program has been very effective for reducing substance misuse more generally through educating youth with at-risk personalities, motivating them to make changes and helping them develop the skills they need so they are less likely to turn to drugs. Ěý

The program, which in this case will work with Grade 10 students, identifies four at-risk personalities — sensation seeking, impulsive, depression-prone, and anxiety sensitive. In Dr. Stewart’s earlier studies, focused on alcohol and illicit drug use, personality factors tended to predict the likelihood of substance use and escalation in use.Ěý Her more recent research shows links of these same personality traits to prescription drug misuse. Some work has shown that starting the Preventure program early before young people have started using illicit drugs even has some preventative effects.Ěý The CRISM project will test whether the Preventure program has preventative effects for opiate misuse.

While not as prevalent as marijuana use, Dr. Stewart points out that some statistics suggest prescription drug misuse in young people is second only to use of pot. There are many pathways to opiate misuse, from legitimate prescriptions for pain relief to stealing it from parents or buying it off the street. Then there are those unintentionally exposed to it through other drugs cut with substances like fentanyl — sometimes with fatal consequences.

“They might be using another drug entirely and didn’t realize it’s laced,” says Dr. Stewart. “That’s another reason we think prevention is so important, because if you can reduce any forms of substance misuse we might be able to have an impact on the opiate crisis.”

Matthew Herder

Director, Health Law Institute

Determining the causes of the opioid epidemic in North America is a tricky business, but there’s a growing movement afoot in Canada’s medical and legal communities to shine a light on the role aggressive marketing of opioid products played along the way.

That’s the aim of a series of open letters sent last month to the Attorney General of Canada and the federal Minister of Health by several Canadian experts, including Matthew Herder, director of Dal’s Health Law Institute and a cross-appointed professor in the Faculty of Medicine and the Schulich School of Law.

In the initial letter, Prof. Herder and the others encouraged the federal government to carry out a criminal investigation into the marketing of opioids in Canada and to “directly compensate victims” of the crisis with funds recovered from manufacturers. It pointed to the guilty plea of major opiate producer Purdue Pharma in the United States for illegally marketing the drugs, suggesting inappropriate practices by the firm likely took place north of the border as well. The letter points out that Canadian prescribing rates for these medications accelerated with the Canadian opioid-related death rate, and two more letters were sent with other evidence, but so far with no official response from the government.

In the initial letter, Prof. Herder and the others encouraged the federal government to carry out a criminal investigation into the marketing of opioids in Canada and to “directly compensate victims” of the crisis with funds recovered from manufacturers. It pointed to the guilty plea of major opiate producer Purdue Pharma in the United States for illegally marketing the drugs, suggesting inappropriate practices by the firm likely took place north of the border as well. The letter points out that Canadian prescribing rates for these medications accelerated with the Canadian opioid-related death rate, and two more letters were sent with other evidence, but so far with no official response from the government.

Ěý

“The drug regulatory system has in many ways let us down in terms of failing to anticipate the level of risk with these products, and as that risk around addiction became known, failing to respond to how those products were marketed in Canada,” says Prof. Herder.

Prof. Herder’s own research in this area, funded through a CIHR grant, focuses on ways to encourage more transparency and enforcement in Canada’s drug regulatory system.

“A lot of my research is designed for advocating in favour of opening up that information so you can have more eyes on it,” he says. “This case provides a really powerful example of how, perhaps, if that information had been more transparent maybe somebody might have identified these problems earlier on, or to be able to hold the regulator to account to enforce the law earlier on.”

Read also:

While some Canadian victims of the opioid crisis have launched a civil lawsuit against Purdue, Prof. Herder says the settlement offer they’ve received — still under review by provinces and territories — falls far short of what they expected or deserve.

He says if the government is serious about deterring similar conduct in the future, new legislation, strategies and practices are needed to encourage compliance with Canadian law. Ěý

“It’s more about changing the practice and less about the actual penalties involved,” says Prof. Herder. “It’s pretty clear that there isn’t any obvious legal mechanism by which we are going to be able to cover the cost the opioid crisis has wrought upon Canadian health care systems.”

Karen Foster

Canada Research Chair in Sustainable Rural Futures

Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology

The film Werewolf, and a noteworthy portion of the discussion regarding opioid use, connects with issues faced by rural communities.

“We don’t know for sure, but rural communities are probably not any more likely to face drug problems than urban communities,” says Karen Foster, whose research explores the sustainability of rural life in Atlantic Canada.

“We don’t know for sure, but rural communities are probably not any more likely to face drug problems than urban communities,” says Karen Foster, whose research explores the sustainability of rural life in Atlantic Canada.

Dr. Foster says some of the public worry about opioids in rural communities — fueled, perhaps, by dialogues in the United States — echoes the way rural communities with high unemployment have been seen as a risk area for drug use (first alcohol, now illicit drugs) by policy makers for centuries, back to the dawn of industrialization and urbanization.

The more serious concern related to drug use, she explains, is in access to treatment.

“The real problem emerges where, in a rural community, you won’t have access to emergency care in the event of an overdose and you may not have access to ongoing counselling, safe ways of using drugs in support places, etc. In a rural community, you’re more likely to be using opioids in a more isolated way.”

In her conversations and focus groups with individuals who live in rural communities, Dr. Foster says there’s an acute awareness that the choice or the fact of living outside of the city means they don’t expect to have a specialist living down the street.

“But what they’re worried about is seeing basic services, including emergency services, withdrawn from rural communities,” she says. “There are places in Nova Scotia where the emergency room is only open certain days a week — and an emergency doesn’t pick when it’s going to happen. In the case of an overdose on opioids, where you may not have very long to reverse the effects, not having an emergency room within driving distance is probably going to kill someone.”

She hopes the evolving discussion about drug use continues to take the particulars of the rural experience into consideration, and approaches them with empathy.

“The [rural] context shapes outcomes for people and their treatment options. A lot of the problems that present themselves in cities and are quite obvious — like homelessness but also drug use — are hidden in rural communities. The rural drug user’s experience is not as well known to us, culturally, as is the urban drug user’s experience. There aren’t many movies or TV shows or other cultural productions that depict the rural drug user.”