Winterâs final gasp may have Maritimers longing for a heatwave â but probably not the kind that Dal Oceanography professor Eric Oliver is concerned about.

, led by Dr. Oliver (pictured left), has found that marine heatwaves have become longer and more frequent over the last century. The research shows that annual marine heatwave days have increased by 54 per cent from 1925 to 2016, with an accelerating trend since 1982.

âThis means a marine ecosystem that used to experience 30 days of extreme heat per year in the early 20th century is now experiencing 45 marine heatwave days per year,â says Dr. Oliver. âThat extra exposure time to extreme heat can have detrimental effects on ecosystem health, with impacts on biodiversity as well as economic activities including fisheries and aquaculture.â

Waves of threatening warmth

Marine heatwaves are defined as prolonged periods of unusually warm water at a particular location. Much like the worrying atmospheric heatwaves that make headlines each summer around the world, marine heatwaves are of concern, too.

In fact, a number of recent marine heatwave events have had significant impacts on marine environments. In 2011, a marine heatwave off Western Australia caused an ecosystem shift from being dominated by kelp to being dominated by seaweed, a shift that remained even after water temperatures returned to normal â signalling a long-lasting or even permanent adaptation and change in environment. And in 2012, a marine heatwave in the Gulf of Maine disrupted the lucrative lobster fishery by flooding the system with early landings, which led to an unexpected and significant drop in price.

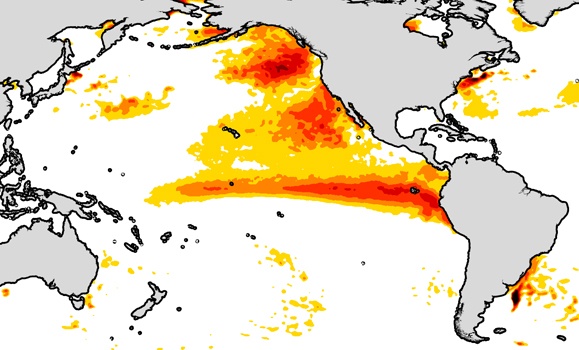

More recently, a persistent area of warm water in the North Pacific lasted for years (2014-2016), causing everything from fishery closures and mass strandings of marine mammals to harmful algal bloom outbreaks along the coast. It even changed large-scale weather patterns in the Pacific Northwest.

Assessing long-term trends

In collaboration with researchers at institutions in Australia, the U.S. and the U.K., Dr. Oliver and colleagues analysed satellite and in-situ observations of sea surface temperature from 1900-2016 and showed that between 1925-1954 and 1987-2016 marine heat-wave frequency has increased by 34 per cent and marine heat-wave duration by 17 per cent globally. They attribute this to a global increase in mean ocean temperatures, and while internal variability plays a role at the regional level, it does not affect long-term trends.

Several of the researchers involved in the heat wave study at a workshop in Perth, Australia in 2015 (Thomas Wernberg photo)

âImportantly, the long-term changes in marine heatwaves can be mostly explained by increases in ocean temperatures, globally,â says Dr. Oliver. The authors suggest that, given the likelihood of continued ocean surface warming throughout the 21st century, and the accelerating trend observed in recent decades, we can expect a continued global increase in marine heatwaves in future, with important implications for marine biodiversity.

âWe will continue to see impacts on our marine ecosystems, making them less stable and predictable,â explains Dr. Oliver. âThese are systems that many around the world rely on for food, livelihoods and recreation.â

Looking backwards and forwards

Part of the difficulty in this study was the lack of data on the ocean.

âWe needed ocean temperature measurements resolved daily. But on a global scale, thatâs only been available since the early 1980s when satellites first began observing the ocean surface,â says Dr. Oliver. âBut a few sites around the world have daily measurements going back to the early 20th century, and we also have monthly measurements of sea surface temperatures globally going back over a similar period.â

The research team was able to borrow information across these three sources of data to piece together a single global record of marine heatwaves, going back to the early twentieth century, for the first time ever.

âOur next step is to quantify what the future changes will be. To do this we need to use computer models of the worldâs climate, and calculate what the global state of marine heatwaves is projected to be going forward, in the 2050s, in 2100, etc. This is an important study we are now working on.â

More information on this and related studies can be found at .