Award-winning HÂţ» PhD student Simon Gebremeskel is a pioneer in discovering how the immune system can fight cancer.

“The more we know, the more we realize we don't know. We're only starting to scratch the surface,” says says Gebremeskel who, as top-prize winner at this year’s Canadian Student Health Research Forum, has earned himself a coveted nomination to attend the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in Germany in 2018.

Cancer-killing combo

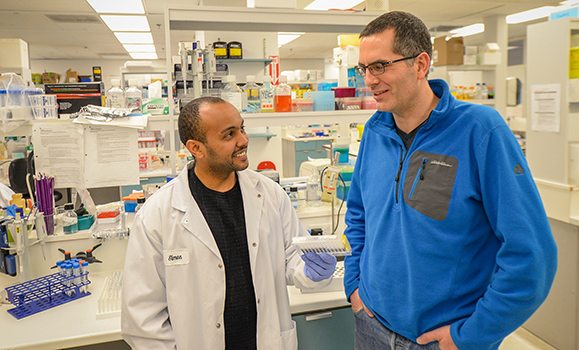

Gebremeskel is working with Dr. Brent Johnston in HÂţ» Medical School’s Department of Microbiology & Immunology to develop a cancer treatment that kills cancer cells by both activating the immune system and introducing viruses that kill cancer cells. This novel combination strategy — of immunotherapy plus oncolytic viruses — could be available within a few years.

Simon Gebremeskel with Dr. Brent Johnston.

In fact, Gebremeskel predicts people with cancer will be treated entirely differently within “the next decade or so,” once the costs of groundbreaking new treatments come down.

The beauty of cancer immunotherapy is that side effects are not as severe as those in surgery, chemotherapy and radiation. And, there is evidence the immune system “remembers,” so it will fight off new attacks by a returning cancer.

It's a cops and robbers story with scientists racing towards a cure while devious cancer cells try to outwit the immune system.

Cancer as immune deficiency disease

“What's becoming clear in the field of cancer therapy is the majority of cancer patients should be looked at as patients who have immune deficiency,” says the Kenyan-born scientist, who did his undergraduate degree at Queen's University. “Normal cells in our body become transformed quite frequently into pre-cancerous or early-stage cancer cells. Evidence suggests the immune system is able to recognize these changed cells and clear them off.”

As Gebremeskel explains, cancer erupts for two reasons: “The immune system fails to recognize the changed cell, which is now cancerous, and the new cancer cell turns off the immune system, essentially enabling it to proliferate without any checks and balances.”

The two-pronged approach that Gebremeskel and the team in Dr. Johnston’s lab have developed helps the immune system fight cancer in two ways. First, they use viruses to infect and kill cancer cells in a way that makes any remaining cancer cells visible to the immune system. “Second, we use compounds that activate the immune system to help it overcome any attempts to shut it down,” he says. “The challenge will be convincing clinicians that you get a better response when you combine these two approaches.”

The Johnston lab is working with melanomas and breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancers, investigating when to introduce each approach.

“We know giving the virus first works, but is that the best outcome? If we flip the order, would we get an even better therapeutic benefit? We don't know yet.”

An emerging research superstar

A specialist in immunology who first worked in autoimmune diseases in Toronto at St. Michael's Hospital, Gebremeskel was drawn to HÂţ» in 2011 by Dr. Brent Johnston and his work in cancer immunotherapy.

“He seemed to be a young and energetic investigator who was working in a very new and exciting field,” says Gebremeskel, adding, “The other reason I came to Halifax was because I fell in love with the city when I was here in 2009 for Paul McCartney's concert… I came and I loved the people and haven't looked back ever since.”

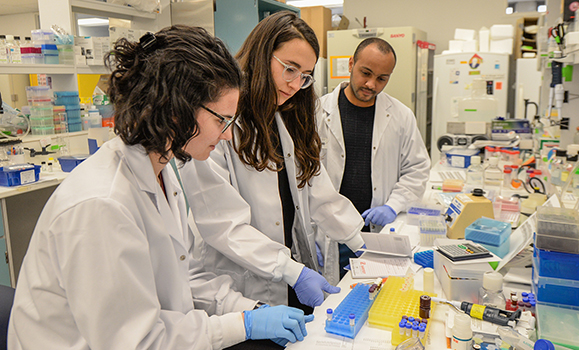

Gebremeskel with Tora Oliphant and Brynn Walker, senior undergraduate students in the Department of Microbiology & Immunology.

Gebremeskel won a research excellence award from HÂţ» Medical School in 2016 and . After that, he was chosen to attend the Canadian Student Health Research Forum in June in Winnipeg. Over two days of competition with 300 other students, he emerged as the top winner, who receives the Lindau award. The top three winners were invited to the Gairdner Awards gala in Toronto, which celebrates international biomedical scientists.

“I got to meet people that I have only read their work or was aware of their discoveries,” says Gebremeskel, who attended the Gairdner Gala this November. “What was encouraging from these various events was learning that not everyone has a linear path… some of these people were very open about the failures they'd had in their careers.”

Gebremeskel, who defends his PhD thesis this spring, is a bright light at HÂţ». “He is outstanding,” says Dr. Roger McLeod, associate dean of research at the medical school. “His work is absolutely groundbreaking… he's one of the best students we’ve ever had in our graduate studies program… in no small measure due to his research skills and dedication to HÂţ».”

A love of teaching matches Gebremeskel’s love of research. He has mentored many undergraduate students in Dr. Johnston's lab and describes the experience as “most rewarding.” “We take on way more students than most laboratories would,” he says, “mostly because I recognize the need to offer these opportunities to students as early as possible, so hopefully many continue to work in the field and get excited about it.”

“If I can ever find a position that will allow me to do the research and continue to mentor the next generation of scientists, that would be a dream position.”

Editor's note, Dec. 11: This story has been updated to clarify the nomination process for the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting.