Jane Allin loves kayaking. A lot. She often spends up to four hours a day on the water when sheÔÇÖs at her home in Port Medway, a community on Nova ScotiaÔÇÖs South Shore about 30 minutes outside of Bridgewater.

Last year, the retired elementary school teacher and principal (who splits her time between Nova Scotia and Ontario) added an extra task to her paddles on the ocean. It all started when JaneÔÇÖs husband came across an article in a local newspaper about a H┬■╗ş researcher looking for help counting jellyfish. Jane reached out and, before she knew it, was contributing to a region-wide study on jellyfish patterns, part of a broader effort to better understand feeding habits of the endangered leatherback sea turtle.

ÔÇťItÔÇÖs made me more curious,ÔÇŁ says Jane, who is now in her second year counting and tracking jellyfish. ÔÇťYou start with jellyfish, and you start finding other things youÔÇÖd never noticed before.ÔÇŁ

ÔÇťItÔÇÖs made me more curious,ÔÇŁ says Jane, who is now in her second year counting and tracking jellyfish. ÔÇťYou start with jellyfish, and you start finding other things youÔÇÖd never noticed before.ÔÇŁ

Another South Shore resident, Judy Bowers, does her jellyfish counts from land. She and her husband walk the sea shore frequently, but itÔÇÖs on Mondays that they do their count. He brings the measuring tape ÔÇö┬áto track the size of beached jellyfish ÔÇö while she takes the notebook and documents what they find.

ÔÇťBefore they were just little blobs on the sand,ÔÇŁ says Judy. ÔÇťNow I know what they are, and a bit more information about them. It makes our walks more interesting too.ÔÇŁ

Jane and Judy are two of more than 50 ÔÇťcitizen scientistsÔÇŁ across Atlantic Canada contributing their eyes, and pens, to Dal student Bethany NordstromÔÇÖs masterÔÇÖs project this summer. Their collective efforts represent an engaging, community-based solution to the challenge of tracking the elusive jellyfish.

Understanding turtle feeding habits

ÔÇťElusiveÔÇŁ might seem a strange phrase to describe a creature that pretty much everyone has seen on the beach at one point or another. But, as Bethany explains, jellyfish are notoriously difficult to research.

ÔÇťA turtle, for example, you can put a tracker on it, follow it, get a sense of their migration patterns,ÔÇŁ she says. ÔÇťBut jellyfish show up sporadically with little warning, and can disappear just as quickly.ÔÇŁ

There are many reasons why researchers like Bethany would want to better understand how and when jellyfish appear off our shores,┬áfrom public safety (their stings can pack a small-but-mean punch) to environmental concerns (jellyfish are often an indicator species that helps illuminate different facets of ocean health). But BethanyÔÇÖs particular interest concerns an annual visitor to the North Atlantic: the leatherback sea turtle.

Each summer, Atlantic Canada hosts one of the highest density of foraging leatherbacks in the North Atlantic, as the endangered turtles swim north from tropical waters specifically to feed on jellyfish. The leatherbacks have fascinated Bethany ever since she was little.

ÔÇťI grew up in southern New Brunswick, just off the Bay of Fundy, and as a kid I was really obsessed with frogs and creepy-crawly things and also the ocean,ÔÇŁ she says. ÔÇťSo when I found out there was a reptile that lived in the ocean and that was close to our waters, I was really excited and then became slightly obsessed with them.ÔÇŁ

ÔÇťI grew up in southern New Brunswick, just off the Bay of Fundy, and as a kid I was really obsessed with frogs and creepy-crawly things and also the ocean,ÔÇŁ she says. ÔÇťSo when I found out there was a reptile that lived in the ocean and that was close to our waters, I was really excited and then became slightly obsessed with them.ÔÇŁ

After completing an undergrad degree in wildlife conservation at the University of New Brunswick, Bethany came to H┬■╗ş to study with along with Mike James, a Department of Fisheries and Oceans researcher whoÔÇÖs the leading expert in Canadian sea turtles. (Bethany also works in collaboration with the .)

Together, they identified the turtlesÔÇÖ prey field as an area worthy of further research. By studying the turtlesÔÇÖ main food source ÔÇö┬ájellyfish ÔÇö Bethany is hoping to learn more about theirÔÇÖ feeding patterns. In particular, sheÔÇÖs interested in the spatial and temporal patterns of jellyfish in Atlantic Canada, and what size jellyfish patches are required to attract and retain the turtles in a certain area.

Engaging the community

Which brings us back to BethanyÔÇÖs jellyfish challenge: how do you study an organism thatÔÇÖs so difficult to track?

Part of her solution is to focus a portion of her efforts on a known leatherback foraging ground: an area of the ocean off the coast of Cape Breton where leatherbacks have been studied for over 15 years. SheÔÇÖs spending time there this summer using acoustic technology to try and determine just how many jellyfish there are under the waves. (The turtles dine on their prey at the surface, but they bring them up from the depths.)

ÔÇťBut in order for me to look at jellyfish across the Atlantic Provinces, we quickly realized I wasnÔÇÖt able to do it by myself,ÔÇŁ Bethany explains. ÔÇťI wasnÔÇÖt going to be able to be out visiting 40 sites across the provinces on boats and beaches looking for jellies.ÔÇŁ

It was Dr. Worm who suggested using citizen science ÔÇö a blanket term to describe involving the general public as active participants in scientific research. The idea was to find community members around the Atlantic provinces who would report back to Bethany about jellyfish they were seeing in their waters. Last summer, Bethany spent a couple of months seeking out volunteers. She did TV interviews, spoke with radio stations, and pitched local community newspapers for coverage.

ÔÇťAt first I was a little bit skeptical; I wasnÔÇÖt sure who would commit to wanting to do these surveys,ÔÇŁ she says. ÔÇťBut I couldnÔÇÖt believe how many people responded and said they wanted to.ÔÇŁ

After a successful summer, many of the volunteers ÔÇö┬álike Jane and Judy ÔÇö┬áhave returned for a second season of jelly-watching. Bethany mails each of them a jellyfish monitoring kit, which contains the data sheets to fill out along with rulers, gloves and a guide to different species of jellyfish. The volunteers are expected to fill out their data sheets weekly, and while theyÔÇÖre not required to report to Bethany each week, many do so.

Bethany also accepts info on jellyfish sightings from anyone, anytime, on what she calls her ÔÇťjellyfish hotlineÔÇŁ ÔÇö┬áa jellyfish@dal.ca email address.

ÔÇťThere are so many people these days interested in getting involved in science,ÔÇŁ she says of her approach. ÔÇťI think a lot of it has to do with all the information coming out on climate change, and hearing about biodiversity crises and whatnot in the news. People are becoming more and more engaged and want to know what they can do to help.ÔÇŁ

Stings and other things

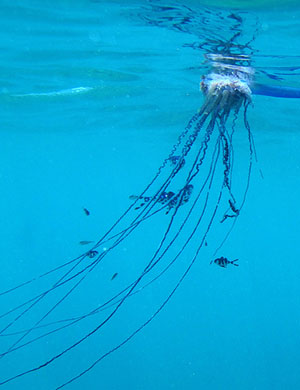

In the process of finding and organizing her volunteers, Bethany has become a go-to expert for journalists and others looking to learn more about jellyfish. That led to a bunch of interviews this summer when sightings emerged of Portuguese man oÔÇÖ war in Nova Scotian waters.

ÔÇťTheyÔÇÖre actually a siphonophore ÔÇö┬átheyÔÇÖre related to jellyfish, but belong to a different order,ÔÇŁ explains Bethany, who says sheÔÇÖs not surprised that the creatures ÔÇö rare to our shores ÔÇö garnered such attention, given their reputation.

ÔÇťTheyÔÇÖre actually a siphonophore ÔÇö┬átheyÔÇÖre related to jellyfish, but belong to a different order,ÔÇŁ explains Bethany, who says sheÔÇÖs not surprised that the creatures ÔÇö rare to our shores ÔÇö garnered such attention, given their reputation.

ÔÇťTheyÔÇÖre really pretty, but they are dangerous, so I see how people reacted in such a way. But it was important to do all these interviews because many people seemed to think that their stings are fatal, which isnÔÇÖt necessarily true.ÔÇŁ (While the man oÔÇÖ warÔÇÖs sting is much more severe than your traditional jellyfish, deaths usually only occur in rare cases where the venom causes an allergic reaction.)

Bethany herself has yet to be stung by any sea creature, even the jellyfish sheÔÇÖs been researching for two summers. But as she looks ahead to completing her thesis over the next year, and ahead to what she hopes are further adventures in marine science, sheÔÇÖs optimistic that her work will have an impact on the sea turtles that first inspired her so many years ago.

ÔÇťWe have one of the largest foraging populations here in our Atlantic waters. ItÔÇÖs critical that we understand the habitat that theyÔÇÖre using and their requirements, so we can continue to protect this area for them.ÔÇŁ

Photo credits:

Beach photos: Danny Abriel

At-sea photo: Canadian Sea Turtle Network

Jellyfish photo: Derek Keats (used under Creative Commons license)

Leatherback sea turtle photo: Scott R. Benson, NMFS Southwest Fisheries Science Center (used under Creative Commons license)

Portuguese man 'o war photo: Sean Nash (used under Creative Commons license)