Halifax Member of Parliament Andy Fillmore was on campus last week on behalf of the Honourable Jim Carr, Canada’s Minister of Natural Resources, to announce new funding for research on assessing methane emissions from old fossil fuel extraction sites in two Maritime provinces.

Called legacy sites, these mostly abandoned areas — like coal mines, for example — could be targeted for future remediation, helping the provincial and federal governments develop effective methane management policy and regulations in the fight against climate change.

“Canadian universities are home to some of the best minds in the clean energy sector and they're keen to support our country's transition to a low-carbon future,” said Fillmore. “By investing in the work of these leading researchers, our government is taking meaningful climate action to ensure the accurate and effective measurement of methane emissions in our region.”

Addressing greenhouse gases

A staggering number of abandoned mine openings have been documented in Nova Scotia alone — records go back as far as the end of the 18th century. It’s possible that many of the 1,922 coal mines on record could be releasing methane, a potent greenhouse gas more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide or water vapour. While regulations for shutting down a modern extraction site are in place now, many of these historic sites were built or abandoned generations before current policy existed.

After the Paris climate agreement countries around the world committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. If stagnant, out-of-operation fossil fuel extraction sites are contributing to the problem it’s important to understand how and to what extent. With limited scientific evidence of how much methane could be seeping into the atmosphere from these legacy sites, there’s no real starting point for potential remediation planning.

“Different types of coal have different levels of methane emissions, and there’s currently no record of methane emissions from different mining sites in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick,” explains Grant Wach, geology professor with the Department of Earth Sciences. “Our research aims to build an inventory of methane emission estimates from mines as well as other oil and gas extraction sites in both provinces.”

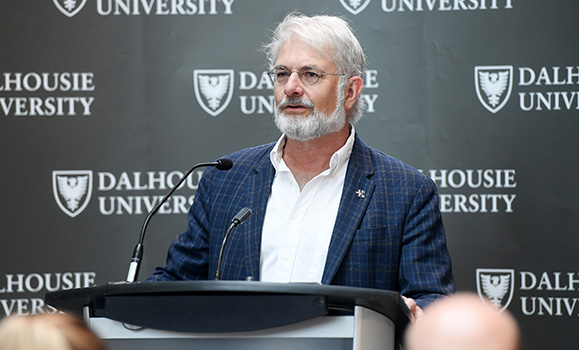

Grant Wach speaks at the announcement event. (Danny Abriel photo)

With $482,000 in funding from Natural Resources Canada’s Energy Innovation Program, Dr. Wach’s Basin & Reservoir Lab is joining forces with researchers at St. Francis Xavier University (St. FX), University of New Brunswick (UNB), University of Waterloo and industry partners like Eosense to tackle the Gas Seepage Project (GaSP) — the first of its kind in Canada. It’s phase one of a methane mitigation initiative in the Maritimes focused on legacy sites.   Â

Identifying “legacy sites”

During the Carboniferous Period over 300 million years ago, the climate was far warmer, with greater amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The warmer climate and atmosphere allowed vegetation and forests to thrive. The Maritime provinces as we know them today were also located much closer to the equator at the time. As plant life died and decomposed in the ancient Maritimes, geological processes of high heat and pressure turned the plant material to coal over hundreds of thousands of years.

Fast forward to the Industrial Revolution, when the sudden demand for coal led to the development of mines in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick during the 18th and 19th centuries.

When new technology and fuels were developed, coal mines in the Maritimes largely became a way of the past and many were shut down. Methane is naturally occurring in coal, meaning any legacy sites that stopped operating before environmental safeguards were put in place could be releasing the gas.

Dr. Wach’s team at HÂţ» and experts at UNB will comb through historical provincial records, maps and satellite images to capture as much information about the locations of these legacy sites as possible. They’ll examine associated geological features underground, which are important for considering how to mitigate methane emissions in any future remediation plans.

“This project is unique,” said Fiona Henderson, research assistant on the project and recent HÂţ» graduate. “It has an all-encompassing, holistic approach to the problem [of methane emissions].”

A cross-university, cross-sector collaboration

Data on the legacy sites’ locations and geology will then be handed over to teams at St. FX and UNB, who will conduct field work with locally-developed sensing technology from industry partners like Eosense to detect and measure methane emissions associated with sites. Similar projects are in progress in the United States and Europe.

Eosense representatives explain sensing technology to MP Andy Fillmore, joined by Grant Wach of HÂţ» University and Dave Risk of St. FX.

“Being part of such a diverse, methodological study is very exciting for us,” said Colleen Gosse, a research and development engineer with Eosense and master’s student in engineering at HÂţ» who attended the event to demonstrate how the technology used in this research works.

“The range of fields being brought to bear on this one project is just fantastic,” said Chance Creelman, vice president of research and development at Eosense, who joined Gosse at the announcement.

With Canada’s first-ever provincial-scale methane emissions estimate inventory in hand, the research team will also have a detailed approach to the technologies and methods required to complete such a project.

“Through GaSP, HÂţ»â€™s excellence in earth sciences research is united with the strengths of other Canadian universities and industry partners,” said Ian Hill, associate vice-president, research at HÂţ».

“Together, and with this federal support, we’re building the scientific knowledge required to better understand how the fossil fuel extraction sites of our past are still affecting our atmosphere today. This research will also lay the groundwork for similar methane emission assessments in other areas of Canada and the world.”