For Jonathan Franklin, a PhD candidate in the Department of Physics and Atmospheric Science, making the transition to Halifax and HÂŝğ from his home just south of Boston, Massachusetts âwas easy,â he says.

Perhaps a bit easier than the transition at the end of May from rainy springtime in Halifax to snowy Igloolik, Nunavut. But Franklin, who works with on climate change and pollution research, jumped at the chance to participate in a week-long education outreach program organized through (the Canadian Network for the Detection of Atmospheric Change).

Back in May 2010, Franklin took part in his first outreach experience in Pond Inlet, Nunavut. This yearâs trip to Igloolik âwas more student-centred,â says Franklin. âWe spent a lot of the time interacting with them in small groups, rather than just presenting information to them.â

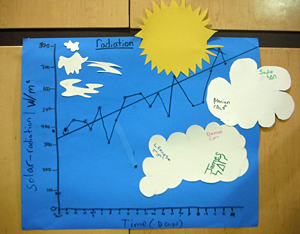

The May trip was follow-up to one in March, when another group of graduate students visited Igloolik to show school children how to build simple measurement tools. That outreach team left basic thermometers, pyranometers and anemometers for the children to use to gather basic data about the temperature, solar radiation and wind.

Franklin â along with two other university students, Anthony Pugliese (at the University of Toronto) and Melanie Wright (a masterâs student at Western University), and with the CANDAC outreach co-ordinator, Ashley Kilgour â helped the kids interpret the data theyâd been gathering since March. Franklin and his colleagues also helped the kids decide how to share their data with other classes and with people in their community.

Franklin â along with two other university students, Anthony Pugliese (at the University of Toronto) and Melanie Wright (a masterâs student at Western University), and with the CANDAC outreach co-ordinator, Ashley Kilgour â helped the kids interpret the data theyâd been gathering since March. Franklin and his colleagues also helped the kids decide how to share their data with other classes and with people in their community.

âSome wanted to make a story, some wanted to draw pictures of a specific day they took measurements, and one group even made a video,â Franklin says. âThey filmed the process of setting up the pyranometer to measure solar radiation and did the editing after.â

âThe kids really enjoyed doing something different,â he continues. âThey were enthusiastic and invested in it, because theyâd spent the time going out in the cold to take these measurements. They were very enthusiastic; it was very effective.â

Helping budding atmospheric scientists

These interactive opportunities have been part of the Arctic outreach programâs mandate since its inception in 2004. Kaley Walker, associate professor in the Department of Physics at the University of Toronto, was part of the team that started the program â almost more by accident than intention.

âThe CANDAC outreach program grew out of an outreach program that started when the first ACE Arctic Validation Campaign team got stuck in Resolute Bay [Nunauvut] because of a snowstorm,â explains Dr. Walker. âTwo of the team stayed up talking with the principal from Qarmartalik School.â

âBy the time I got up the next morning, we were going to spend the day at the school and I was to give a talk about what we were doing in Eureka,â she says. That led to several subsequent visits, âwith the goal of not just talking 'at' the students. We developed workshops and activities for the classes to complement their science curriculum materials.â

This year in Igloolik, the school children learned how to make simple recording tools, went outdoors in frigid temperatures to take measurements, and recorded their data for future use.

This year in Igloolik, the school children learned how to make simple recording tools, went outdoors in frigid temperatures to take measurements, and recorded their data for future use.

They were also encouraged to think about whether or not their data was accurate. âSometimes the data is ânoisy,ââ Franklin explains, noting one group that took anomalous readings. So he asked them what they think happened and whether the measurement is believable. âWith just a bit of prodding, they start thinking, âWait a minute, whatâs going on here?â With older kids, anyway, we could have discussions about data quality and problems with the instruments. âMaybe a wire was loose?ââ

Ìŭ

On the last day, a big assembly was organized in the school gym. âThey put up all their various graphs, stories, videos documenting their data collection. All the classes came, and some of the kidsâ families and parents,â Franklin says. âAnd in the corners, they had demo stations to show their parents what theyâd been doing.â

Observing, quantifying â and sharing

Franklinâs own objectives for doing outreach arenât much different from those of the program: âI want students to pay more attention to the world around them, to see whatâs going on, but also to be able to quantify it in some way â to note the first time the snow buntings arrive, for example.â

âUp there, children are a bit more in tune with the cycles, in the way they live. Those observations already exist,â Franklin says. âI asked a 10-year-old when the ice was going to break, and he didnât blink: âBy the end of June.â So they have a sense of the cycles already. But itâs also important to be able to share your observations.â

âAnd maybe theyâll learn that people can make a living sitting there and staring at the weather,â he says with a grin.

âThe changing climate does directly connect to their way of life,â he says. âMany families still hunt, so they see the changing seasons over their lifetimes. And any changes will affect them much more than children down here. So itâs important to make sure theyâre paying attention to whatâs happening around them.â

Visit to learn more about the programâs goals and to find .

about the trip to Igloolik.