|

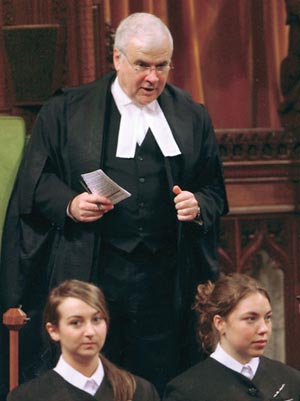

| Speaker of the House Peter Milliken. |

Peter Milliken is in a hurry.

A vote has come up in the House of Commons, which is why the Speaker of the House is rushing to tie up his parliamentary dress when I enter his library-like office. He apologizes that he might have to cut our interview short, a prospect which worries me: I have a whole slew of questions to ask Canada’s longest-serving Speaker, not only about his time as a HÂţ» student but about the unique experience of overseeing Parliament through 10 tumultuous years of political history.

My worries vanish as Mr. Milliken takes a seat and starts answering my questions with clinical precision: short, succinct, charmingly utilitarian. The man has efficient conversation honed to a science.

It’s possibly the only way to survive as Speaker. Lest you think that the job begins and ends at question period, Mr. Milliken runs me through his agenda for the day. Even though the House isn’t formally sitting, it’s still chockfull: four receptions, including one at the National Gallery; plans for both lunch and dinner (the latter an event he’s hosting, no less), several important correspondences to respond to...oh, and the vote in the House that just came up. He doesn’t expect to make it back to his residence until late evening.

“The hours,” he answers without hesitation when asked his least favourite part of the job. “If I’m lucky I’ll get a morning at home in Kingston on the weekend. But usually the weekends are pretty busy as well.”

On one of those weekends, a few weeks after we spoke, he told a hometown crowd of friends, family and supporters that he will not run in the next federal election. So begins the process of ending a vast and distinguished career in Canadian politics. Few Speakers in our country’s history have made such an indelible mark.

In the House of Commons, procedure makes the Speaker the centre of attention; he’s the conduit through which every debate and cross-floor exchange takes place. ?But he’s often invisible to those of us watching at home, edged out by political soundbites.

There are exceptions. Only 11 times in Canadian history has the Speaker of the House had to cast a vote in the case of a tie; he lays claim to six of those votes, most famously on a 2005 budget amendment that constituted a confidence motion. (As is procedure, he voted “yea” because it moved the matter forward.) And some of his decisions, such as his 2007 ruling allowing an opposition bill on the Kyoto Accord, have earned national media attention.

Even by those standards, though, his ruling on April 27 this year was unique. Citing national security concerns, the minority Conservative government was refusing to share sensitive documents on the possible abuse of prisoners in Afghanistan. The opposition had voted to demand their release. Stuck in a stalemate, the House asked the Speaker for a ruling: does parliament have the authority to demand the documents, or does the government have the right to withhold them?

Many saw this as a potentially landmark decision: a ruling on the balance of power between cabinet and Parliament that may have longstanding implications. But the attention took Mr. Milliken by surprise.

“I didn’t think it would be that big a deal for the media at the time, but obviously, given what happened the next day in the newspapers and on TV, I guess they thought it was,” he says with a modest chuckle. “It got a lot of coverage, which was a bit of a surprise because, generally, my rulings...well...don’t.”

Political watchers tuned in as the Speaker delivered a ruling that affirmed parliamentary supremacy while delaying judgment on whether the government was in contempt. Instead, he urged both sides to work toward balancing the competing concerns. A week later, a compromise was reached.

|

| At work in the House of Commons. |

That sense of fairness – a belief in encouraging cooperation in Parliament – is a trait that has followed Mr. Milliken through his time in office. It’s why he, a Liberal, has continued to earn the support of the House even as the government changed hands to the Conservatives. And it helps explain why the cordiality built into his schedule is so important: if he’s going to command the attention of Canada’s parliamentarians, he also needs their respect.Â

Spending time with fellow MPs is fun as well. “There’s a lot more in there, the House, that’s for show. Most members love to sit down and chat with each other, over dinner or when we go on foreign missions together. They’re really great to work with.”

You’d almost think Mr. Milliken, the eldest of seven children raised in Kingston, was destined to be Speaker; at the very least, a life in politics was an obvious career path. Not only does it run in the family (his cousin is former MP John Matheson), but he was a teenage subscriber to Hansard.

“I think I was in Grade 7,” he recalls. “I had a class trip up and watched the House and I thought it was fascinating. I don’t know how much more I can explain it than that; it’s just something that gripped my interest right away.”

Like many with political ambitions, Speaker Milliken sought out a career in law, which brought him to HÂţ» in 1970 after two years at Oxford.

“Because I was finishing my degree in a single year, I had to take a first-year course in criminal law, to my recollection, and the rest of them were second- or third-year courses. So I got to meet a lot of the students because I was in these different classes for different years.

“I maintain contact with a lot of those students from when I was there.”

Jumping into political life in 1988, he won the Liberal nomination and defeated a Progressive Conservative cabinet minister. He took an immediate shine to parliamentary procedure; his first major speech in the House was on a point of order. Little wonder that when the Liberals took power in 1993 he made his way through several procedure-heavy roles: parliamentary secretary to the government House leader, chair of the Commons procedure and House affairs committees, and deputy Speaker of the House.

In 2001, Mr. Mililken was elected Speaker of the House; as is custom, he was dragged to the chair by the prime minister while feigning opposition.

“I was very keen to do the job but, of course, I resisted, ” he says with a laugh.

In the years that followed, he became renowned not only for his commitment to fairness and good order, but also a dry sense of humour.

He’s modest about his accomplishments, though. Asked what he’d like to be remembered for as Speaker, he returns once again to fairness.

“I guess just the importance of trying to be fair and equitable in the way that you apply the rules of the House to the members when they’re raising issues. I think that’s the basic and most important part. That’s how you keep everyone happy.”Â

Of all the questions I ask Speaker Milliken, he seems happiest answering one that comes spontaneously from a tangent. His eyes light up about reading things other than parliamentary precedent.

“I don’t get to read that many books, unfortunately. I’ve got a great stack of them – and I mean BIG stack – of unread books, because I just don’t get time to read them. I read a lot of magazines. Policy Options, The Economist, The Walrus, Foreign Affairs. That’s how I try and keep up with the news, but just getting through those is difficult. In the summer I’ll get a book or two read, and usually at Christmas time too. But it’s not easy.”

At the end of our conversation, I asked him whether he’d thought about his future after being Speaker; he told me it was a bridge he hadn’t crossed yet. In hindsight, though, I could almost see his gaze turning away from the stoic halls of power on Parliament Hill and towards that pile of books on his desk at home in Kingston.

A political retirement well-earned, he’s got a lot of reading to do.