|

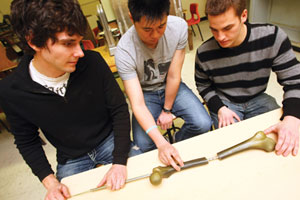

| Riley Wilson, Ziang Gong and Andrew Allan work on their senior design project. (Nick Pearce Photo) |

It’s late at night when most of the city is sleeping and the hospital is eerily quiet. But in the operating room, a tired but undeterred surgeon is struggling through a femoral fracture reduction on a young patient. The surgery, which is usually a meticulous and straightforward procedure, is not going smoothly. After wrestling with the fracture, he has no choice but to take a more invasive approach. He cuts open the femur and reduces the fracture—if not, displaced fat and marrow could cause a fat embolism in the lungs.

“There must be an easier way,” Michael Dunbar, an orthopedic surgeon and professor in the department of surgery, thinks to himself.

Most long bone injuries require a large amount of force to fix and are often the result of a fall or car accidents. To reduce the fracture, surgeons operate remotely from the top of the femur, placing a nail in the medulla—the bone canal—and inserting screws across the top of the nail to keep it in place.

However, if the fracture cannot be properly aligned, the nail cannot be inserted. In these cases the femur must be opened so the bone can be aligned, but this more invasive procedure is regarded as a last resort for surgeons.

“It’s a bit analogous to stripping the bark off a tree,” says Dr. Dunbar. “If you have to open it up, it can delay the healing.”

Driving home that night, Dr. Dunbar came up with an idea he thought would eliminate cutting into the femur. The next day he called second-year medical student Dave Wilson, a HÂţ» biomedical engineering graduate working under Dr. Dunbar, for his advice.

Technically possible?

“He told me we needed something that could be placed down the canal and steer its way across the fracture withstanding the huge forces in the femur and align the fracture,” says Mr. Wilson. “He asked me if I thought it was technically possible, and as a recent engineering graduate, I thought it was.”

Mr. Wilson suggested the mechanical engineering senior design projects to Dr. Dunbar and the two recruited fifth-year students Andrew Allan, Xiang Gong, Michael Lasaga and Riley Wilson to design and build the device for their project.

“We spent about a month coming up with ideas, made a list of pros and cons and sat down with Dave and Dr. Dunbar and chose the best design from there,” says Riley Wilson.Â

The device they came up with – the Femoral Fracture Reduction device – is a stainless steel rod, with a snake-like end segment controlled by wires running parallel through the device. Surgeons then have the ability to steer the rod across a misaligned fracture and tighten the wires and draw it together, facilitating the most difficult part of the operation.

Less invasive

“If we’re successful, it could mean that for the tough fractures you can’t get reduced, there will be a device that avoids cutting open the femur,” says Dave Wilson.

“It won’t be needed for all cases, but when it is, it will reduce OR time, be less invasive, reduce blood loss, morbidity and improve healing – that’s the promise of it,” adds Dr. Dunbar.

The project was awarded the Innovation Award for Life Sciences by HÂţ»â€™s Office of Industry Liaison and Innovation (ILI). The award carries with it a $50,000 prize, used to help with the prototypes and production of the device. Working with ILI, Dr. Dunbar, Dave Wilson and the students have also begun the process of commercializing the device, applying for a patent and getting testing set up to approve its eventual use in practice.

Dr. Dunbar believes the interdisciplinary cooperation is what made this possible.

“This type of collaboration is what stimulates me and makes me very proud to be part of HÂţ»,” says Dr. Dunbar. “The students link us to the other researchers and groups and it’s what the university is here for, and it’s one of the best parts of my job—that academic link and stimulation. It’s clichĂ© but true that I often learn more from them.”