|

| HÂţ» professor Yuri Leving poses with Vladimir Nabokov memorabilia, including photographs of the Russian Ă©migrĂ© author by Horst Tappe and Russian editions of Lolita.(Nick Pearce Photo) |

In the now-famous , 15-year-old Miley Cyrus is suggestively wrapped in a satin sheet, her hair disheveled, her red lips in a pout.

Some say the photo is nothing more than an artistic portrait of a pretty teenager. Others say it’s a disturbing, Lolita-like way for a young girl—let alone a Disney princess who’s every move is watched and emulated by legions of young fans—to be depicted.

But is it really so unusual? In an article published in a new edition of HÂţ» University’s Nabokov Online Journal, Meenakshi Gigi Durham argues the media—from advertisements to Seventeen magazine—are circulating damaging myths that distort, undermine and restrict girls’ sexual progress.

The sexualization of tween girls—which she dubs “The Lolita Effect” in her book of the same name—is part of a larger, marketing effort to create cradle-to-grave consumers. From Bratz dolls to girls’ T-shirts with suggestive slogans (“Sweet Treats,” “That’s Hot”) and the photo of a semi-nude Hannah Montana, it’s an unsettling trend that’s making us all feel disquietingly Humbert Humbertish.

Since the publication of Lolita more than 50 years ago, Lolita has become the favorite metaphor for a child vixen, yet that perception is a misreading of Vladimir Nabokov’s famous novel. Indeed, Lolita does nothing to attract Humbert Humbert’s devouring and doomed passion, as Dr. Durham points out in her essay.

|

| Nabokov also wrote the screenplay for Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film version of Lolita starring James Mason and Sue Lyon. |

“Wľ±łŮłó Lolita, we are entering the mind of this pervert. So it is about the cruelty of this world and is written like that precisely to alert us,” says Yuri Leving, assistant professor in HÂţ»â€™s Department of Russian Studies and editor of the Nabokov Online Journal. Once banned as pornography, the novel is considered a 20th century classic. “Lolita is disturbing and it is meant to be.”

Dr. Leving posted the first edition of the Nabokov Online Journal last summer. With a pince-nez on its masthead, the second edition just went up on April 23, Nabokov’s birthday.

There are contributions in several different languages, including English, French and Russian, and in different formats, including a video installation and an mp3 file, as well as traditional academic articles and reviews. Contributors range from experts like Nabokov biographer Brian Boyd to some of the students from Dr. Leving’s third-year class, simply called Nabokov (). Dennis Kierans, for example, contributed a music video inspired by Nabokov’s works, and Ashley Moran outlines the rules for a board game she created called Nabokov Dozen.Â

“We have tried very hard to make the journal accessible, which I think scholarship should be,” says Dr. Leving. “So that’s the big reason for publishing online.”

The online journal also scored a major coup by publishing a Q&A with Dmitri Nabokov, Nabokov’s son and literary executor, in which he finally announces what he’ll do with Nabokov’s unfinished book, The Original of Laura. His explicit instructions by his father on his deathbed were to destroy the manuscript—written in pencil on 50 index cards— which has been shut away in a Swiss Bank Vault for more than 30 years.

Instead, as revealed in the Nabokov Online Journal, he’ll publish.

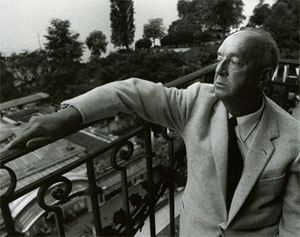

|

| Vladimir Nabokov at Montreux Palace in Switzerland. (Horst Tappe Photo) |

Dr. Leving is enthusiastic about the online magazine; Nabokov’s life and works (10 books in Russian, the final 10 in English) provide a rich legacy for scholarship. He himself first picked up a Nabokov novel as a 17-year-old living in Israel; although he says he didn’t understand what he was reading in the beginning, he became fascinated by the Russian émigré author.

The author of Train Station – Garage – Hangar: Vladimir Nabokov and Poetics of Russian Urbanism, Dr. Leving is now working on two more books, one on how Nabokov used the success of Lolita to provoke public attention and grow his celebrity, and another on Nabokov’s Russian language masterpiece, The Gift. His work is supported by a three-year grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

“What intrigued me then and now too is that Nabokov is an opaque author,” he explains. “He offers challenges on different levels so every reader can find something, depending on their depth of literary insight.

“And then, almost like detective fiction, there are clues and persistent motifs throughout his oeuvre … If you’re an attentive reader, you will find a key to each riddle embedded in the text. You know somewhere there is a key and that’s what makes it so interesting.”

LINKS: | | in The Spectator | in The Times