News

» Go to news main3D printing and the Franken‑lab

A lab where dedicated assistants toil to produce realistic looking skin, skeletons, and other body parts. One wonders what Mary Shelley author of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus would think of the Centre for Collaborative Clinical Learning and Research’s (C3LR) 3D printing lab. ��

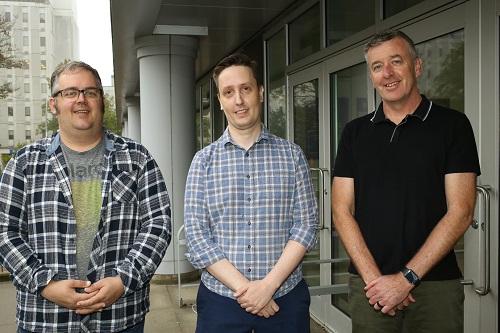

(left-right, C3LR SAs Tom Smith, David Hutton and C3LR director Noel Pendergast. Photo: Bruce Bottomley) �� ��

C3LR simulation assistants (SAs) proposed 3D printing and silicone casting to C3LR Director Noel Pendergast in late 2020. It was a worthy solution to the struggles that the C3LR was facing — as the pandemic broke out, medical equipment was in high demand, resulting in a backlog of products and a rising of prices. Wanting to ensure that pre-existing medical equipment reached the hands of front-line health professionals, C3LR began making prop medical equipment and silicone skin for student simulations.

“This allows us to make simulation props that don’t exist, that we can’t even buy. This has been massive for us,” explained SA David Hutton.

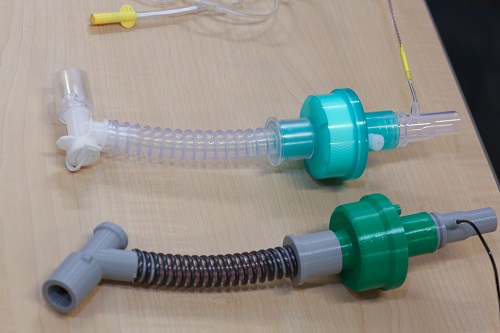

The same weight, shape, and feel of the tools and body parts that students will find in the healthcare workforce, 3D printed and silicone prop supplies proved a financially and ethically sound change to the day-to-day operation of student simulations. Many of the 3D printed objects are completed with the addition of a silicone casting, while other 3D tools are designed to expedite the casting process altogether. Simulation prop tools and body parts are constantly being revised to make them as realistic as possible.

(real medical equipment- top- and 3D printed model at a fraction of cost. Photo: Bruce Bottomley)

(real medical equipment- top- and 3D printed model at a fraction of cost. Photo: Bruce Bottomley)

3D printing and silicone casting have revolutionized the C3LR’s student simulation preparation. “We are able to get a more interesting curriculum through this,” explained SA Tom Smith.��

Thanks to C3LR’s 3D printing and silicone work, simulations appear increasingly like the work that students will do post-graduation, when they will be helping real patients. Always keeping an ear out for recommendations, Hutton and Smith go out of their way to make simulation supplies that are nearly impossible to find elsewhere. Aided by a medicine resident student, Hutton and Smith recently finished making silicone casted pregnant stomachs to be used on mannequins and simulated patients. They have also manufactured chest-tube insertion trainers and broken protruding bones that can be worn by mannequins or people.. Their work ensures that students engage in more wholistically visceral simulations.

The 3D modelling process takes place on a high-tech computer, nicknamed the “C3LR Model Machine”. Hutton and Smith use two programs for 3D design: Fusion 360 and Blender. The former is used for more precise measurements, while Blender is equipped for organic shape design. Hutton and Smith design their own prop medical equipment, body parts and silicone casting tools, occasionally aided by pre-existing 3D models found online. C3LR hopes to start integrating modelling using virtual reality as well.��

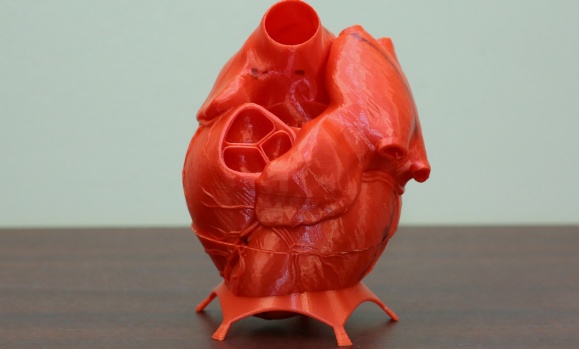

Plenty of artistry is involved in the design process, which can take upwards of 10 hours, depending on the object being created. Hutton and Smith, aided by consultations from heart ultrasound medical professionals, recently completed the 3D design and printing of antamoical models of the four main ultrasound views of the human heart. Hutton and Smith use a PRUSA 3D printer. The machine can print using various sorts of plastics, including ones infused with fibreglass. By designing and printing their own props, Hutton and Smith have greatly reduced C3LR’s simulation equipment spending.

In addition to their use of 3D printing, Hutton and Smith have created the “Franken-lab” — a space where they make fake skin for suturing simulations. Using inexpensive materials, the silicone is tinted to match a variety of skin colours to be placed on simulated patients. The process of drafting silicone skin begins with mixing Part B of the silicone with the pigment, which is then mixed with Part A for two minutes. The compound is then poured into a mold that was 3D designed and printed by Hutton and Smith. In the mold, the compound’s first layer is integrated with a layer of Power Mesh; a stretchy mesh frabric that prevents the sutures from tearing through the silicone when being tired and increases the lifespan of the suture pad. Subsequent layers of silicone are added, each a different hardness to represent the varied densities that compose human skin. The final layer; a sticky silicone gel attaches the suture pad to different surfaces or to a 3D printed suture pad holder. Students prefer Hutton and Smith’s suture pads over the one’s provided from the simulation equipment supplier — they are even asking to buy them from C3LR.

Delighted by Hutton and Smith’s 3D printing and silicone work, Pendergast explained: “it’s so much more sensible — as it is very realistic, more economical, and more ethical”.

��

Recent News

- New aspiring Health Leaders Award invests in the future of health administration

- New clinic set to revolutionize respiratory care in Nova Scotia

- Grad profile: Inspired by the comfort and care of nurses

- Grad profile: Transformative network of support

- Grad profile: A career built on compassion and purpose

- Grad profile: Lifelong passion for serving others

- Grad profile: Leaving space for what comes next

- Grad profile: Taking risks for meaningful growth